Conversations

with: Gordon Massman |

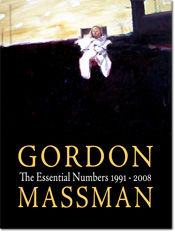

Given that Gordon’s work is profoundly disturbing, in a manner and to a degree that invites even seasoned readers (and fellow writers) to over-identify its speaker(s) with its author, and given that Gordon has, over the last two decades, firmly positioned himself outside of any known school of poetics, never mind any organized network of writers, be it established, academic, small press, micropress, underground or otherwise, and given that Gordon’s book is in many ways new territory for Tarpaulin Sky Press, I thought an interview with Gordon might be in order. Rather than conducting the interview myself—which, as his publisher, would have felt awkward if not incestuous—I decided that Gordon, his work, and his readers would be better served by a more open Q & A format. I asked five people, all writers themselves, to ask Gordon some questions about The Essential Numbers, and that’s all the direction I gave.

Gordon’s answers arrived four hours after I sent the last set of questions to him, three days after the first set. I did not edit them.

--Christian Peet

BLAKE BUTLER: In a book that spans 18 years of writing, how did you select which numbers were most essential to you? What is different about the continuity of those numbers with the others removed—i.e., do you see new gaps, collisions, etc?

GORDON MASSMAN: Three decades ago I heard a quote, whose attribution I have long since forgotten, which fascinated me. It goes something like this: the most effective map is the exact same size as the territory being mapped. I imagine each of four corners of this crinkling paper map floating down to and settling precisely over its corresponding corner so that the map and the land are indistinguishable. This map illuminates for the traveler every vein, rivulet, fissure, and slope; it opens the land’s every pore for meditation and discovery.

Similarly, I find something equally fascinating about the psychoanalytic project—applying the same rigor to the cartography of one’s inner territory. Only in this case the map covers three dimensions and looks more like mist settling over deep plunging glass architectures, inside and out.

Leaving the map metaphor for a moment—at some point in my politics, I lost interest in conventional titles. I felt, and still feel, that the conventional title encapsulates a poem, monumentalizes it, loops its ending to its beginning and pulls tight the chord so that it relates only marginally to the works around it. Putting aside the fact that too many poets use titles, infuriatingly to me, to showcase cuteness, to show us how clever they can be, titles rip words out of relationship into independence, into stubborn free-floating self-sufficiency. This self-sufficiency is antithetical to both maps mentioned above and, ultimately, to what, megalomaniacally, I am striving to accomplish: a related, stitched-together, interdependent covering with language of my entire psyche from the beginning of my revelation until my end. The literal numbers for me are like threads woven together to form this covering, this tarp, if you will. Number 1 hooks onto and winds about number 2, number 2 hooks onto and winds about number 3, number 3 hooks onto and winds about number 4, etc. In short, the entire now one thousand nine-hundred ninety-six pieces (I do not really like to call them poems) are but one single entity, one map, tarp, coating, or whatever you wish to call it. Each number adds length, width, and depth to the one before it.

Finally, to your question. Yes, dropping out large sections of this map forms gaps, rents in the map. These holes force the wanderer to jump over disorienting spaces, from one cliff to another perhaps weeks or months apart. Such omissions take the softness—the safety—out of the singular blanket I am trying to weave. My hubris would prefer, naturally, to publish the entire project without omission in perhaps two volumes: two thousand pages of what I have already completed, and in volume two the final installments I have yet to complete before I die. I would love it if it could be said of me that I attempted the impossible task of transferring myself entire to the world of language, that I replicated all dimensions of myself and, therefore, continued to live, to be known, into perpetuity. How insane is that? How mad?

So sure, unintended collisions exist in this volume which by necessity picks and chooses what Christian Peet, my editor, and I felt were the strongest pieces. I am entirely happy with this. There is, after all, a practical consideration with all art. Some of one’s oeuvre is better than others, one is in better form on one day than another. One must always discard one’s breakage to strengthen the whole.

I am sorry to go on at such length, but please indulge me a little longer. I do not subscribe to the perceived wisdom, the laws of literature promulgated largely by academics and furthered by large segments of the intelligentsia, that poetry and prose are distinct and separate warring genres, to be defended to the death by proponents. For me, at least in modern times, the divisions falls more logically between effective, powerful writing and ineffective, weak writing. What law forces the lyric “poet” into small orgasmic increments while similarly demanding the “prose” writer spin out developed stories. Why cannot a writer, such as I, produce a single voluminous piece, hopefully, of effective, powerful language without being characterized as poet or prosaist. I intend my numbered work to be a single, inner-logical, complex entity, and in that sense, yes, the gaps do disappoint me—practical considerations aside—and create jarring collisions.

BLAKE BUTLER: Do you feel a different person inside your text than you are in your body? Is the writing a focusing of another person, or a removal, or some kind of smudge therein? Or is it something else entirely?

GORDON MASSMAN: I believe the great nerve-work and fiery forge within each one of us almost godly in its omniscience and powers of perception. I believe you, Blake Butler, are murderer, industrialist, mendicant, spiritualist, rapist, whore, misogynist, and lover. I believe you are all human permutations from Hitler to Gandhi. When a man is nailed to a tree for his sexuality or ethnicity, I believe you are both the nailer and the appalled. You both refuse slavery and smoke crack alone in dingy rooms. You are God and The Devil.

I throw as best I can, as believably as I can, the billion colors of human existence through the prism of myself. Over long and intense personal interior struggles I have unearthed my otherwise unspeakable capabilities and visceral dark emotions: rage’s boiling mud, shame’s hot cauldron, the alligators of self-loathing. Not only am I a beautiful child, I am a hideous monster.

Like us all.

Therefore, the person in my body and the person in my text are one in the same. He is me, and I am flinging from my deepest core—making visible—what is universal, I believe, in every male human being. I want my work to spark if not an already conscious embracing, then some subterranean dreamlike ghostly recognition of who you, my reader, are. I want to insist that my sometimes disturbing visions are more or less within everyone, with slight variations. Hasn’t every father fantasized infanticide? Doesn’t every husband want to binge on lovers. Doesn’t murder and suicide lurk in every man?

Like the majority of people, I live a pacifist’s life; I am gentle, tender, soft-spoken, kind. I am generally a courteous and decent citizen. That person, too, resides in my text and body alike; indeed, were he not there to mediate—if he were not infinitely stronger—I would probably not be an intellectualizing writer harmlessly throwing out human colors, but a bona fide miscreant and soul ripper.

ELENA GEORGIOU: What is your latest obsession, and how does it work its way into the poem you are currently writing?

GORDON MASSMAN: Curious you use this word “obsession,” rather, than say, “preoccupation” or “fixation.” To me “latest” implies these latter words and not the former. I’m splitting hairs, but I have a reason. I have been twice hospitalized with obsessive-compulsive disorder; I have battled it for twenty-five years. If it had a physical appearance it would resemble one of those hairless, mountainous, many-fanged monsters lurking at the bottom of a Hollywood pit villains throw men into to die. In reality, it’s a deathless monster wreaking havoc on innocent lives. This kind of clinical monster does not back down or mutate into something else. My clinical obsessions have numbered over thirty at any given moment, which I had to perform in a specific order at threat of having to repeat them beginning with number one, ad infinitum, through the night without sleep or rest. These involve locks, clocks, ovens, toilet seats, numbers, body lotions, dental floss, defecation, urination, noises, bottom sheets, light switches, hunger, toilet paper, and edges of desks. These are bizarre, inexplicable, torturous non-subjects, although the underlying monolithic demon of OCD infuses my work. That is, my death battle with OCD becomes a heightened metaphor in my work for all peoples’ battle against mortality. Hence, the outrage, despair, resignation, viscera, and velocity of my writing.

On the other hand, fixations, preoccupations. My most recent is hubris, the fatal fall in the face of God-aspiration. I think of Herzog’s masterpiece, Aguirre, the Wrath of God. How pathetic human beings look in their ridiculous gear “conquering” a river or a mountain. How pitiful our rocket ships spewing into space, like sparks popping two feet above a campfire. I am amused by the tragedy of megalomania, man’s ridiculous attempt to stick his or her jaw out beyond all others in the bas relief sculpture of squirming humanity.

Other fixations, always there, which I shoot through myself variously depending on life situations are: body weight; sex, death, hedonism, suicide, and parenticide. I usually mix one or more of these sub-dominantly into whatever I am writing, primarily because they are my major subjects.

Your question, how such preoccupations work their way into what I am writing, is a difficult one to answer. This will sound phony or like a parody, but I write in a trance; I literally put my head in my hands, close my eyes, and induce random dream-state imagery, very similar to deep sleep dreams. I can sit in that position for as long as an hour, eyes closed, half asleep, yet monitoring the ribbon of language streaming through me. If something authentic flies by I grab it and hurl it on the screen, at which point I might consciously build on it, but always quickly re-induce this dream state which usually takes the work in unexpected directions. I believe that we all possess a root system of logic, under ground as it were, and that if we harvest it naturally—genuinely—within ourselves, ideas which appear disconnected will in fact be connected and logical. I depend a great deal on the subconscious.

Who has a “poetic sensibility,” who is a natural singer and who isn’t? Who has that indefinable something in their gut, can play words like the virtuoso violinist? That is a question for the gods. Whether I have it, or you have it, or he or she has it, one must summon every ounce of power from within to compose one decent song in ten. All the obsessions, preoccupations, passions, and ideas are fairly worthless without this X factor, this musicality which none of us will ever know if we possessed.

ELENA GEORGIOU: What was the first obsession you tried to explore with writing? Do you still have that piece of writing?

GORDON MASSMAN: My life cleanly broke into two disparate parts, like the Gregorian calendar; my B.C. period—Before Crisis—lasted until I was thirty-four years old and was marked by a measured control and possession of the senses. It was a paradisiacal sense of well-being and youthful confidence wherein everything blossomed and shone for me, producing a fairly standard poetic fare: poems about Mary Magdalene washing clothes in a river or the one who discovered the artichoke or the hurricane I witnessed as a boy or the Beluga whales off the coast of Seward, Alaska. The poems were conventional and composed in the stepped-back object vein of a very clever man with something profound to say. It was capital P Poetry of the sort best exampled by Harvard and Sorbonne graduates such as Richard Howard, Richard Wilbur, John Ashbury, James Merrill, and Jorie Graham—people with intellects and IQs massive enough to win them staggering careers. The rest of us bashed our heads against their wall.

My A.D. period began the moment I accidently tuned into the movie Sybil, about a multiple personality woman and her sadistic mother, which unleashed from my neck high false floor all my weltering monsters. What clawed through the plywood my denial I had nailed over them: primal rage against my parents, my subtly lousy marriage, a horrible self image, resentment toward my young son, and what felt like an unnamable cloud of other demons minor and major. Here began twenty years of psychological battering during which time I developed the demon seed of OCD—my attempt to ward off catastrophe by endlessly performing rituals—and the undergirding for the employment of obsessional subjects in writing.

My first obsession was about insomnia and sleep, as I slept almost not at all for thirteen months, and I still have in a basement box a manuscript of about twenty-five short poems titled, Quarry for Night Howlers, which one could say prefigured the kind of pieces I write today. They are prose poems without stanza written urgently to help me heal. Since the moment the demons cracked through and crawled into my head, writing has been my therapy, my catharsis, and unabashedly I have placed the reader directly behind the psychoanalyst’s couch whatever may come; my poems are psychoanalytical sessions; I have tried to set horror to music for my own benefit. But, I think in my optimistic periods, perhaps others too could benefit from my effort.

SELAH SATERSTROM: Gordon, there are so many commas in the poems. For a couple of years I've been thinking about the energetics of grammar—how those marks/structural hinges constellate the logic that emerges from the syntax in the space/field of the line/lyric. Sometimes in the presence of yr poem's commas, I give them a sound. The terrible gurgle and swish and popping of a function, performing (the animal in the muscle or the sound of deep inner-space, the oceanic echo in meat). Other times the commas feel like gut—a particular texture of connectivity. Sometimes they are like a hot tongue—a kind of, you know, devil tongue (oy): commas as swipe marks, the incessant interruption of which Blanchot speaks. Neither here nor there. But I want to ask you about the comma—the form and narrative speed they contribute to or even co-create in your work. ”Comma”—from koptein "to cut off, " from PIE base *(s)kep- "to cut, split." I suppose what I am really asking you to speak about—to any aspect of—concerns how you experience language on metaphysical and/or visceral levels—its translation through your syntax and marks, into the forms . . . how that happens for you.

GORDON MASSMAN: The man who has been shot doesn’t have time to put on a suit. He’s on the table shouting, “here, here, lower, the gut, oh Jesus, please god though I walk, yea, valley, no evil, fuck, god damn, shit. . . .”

There’s no metaphysics here, no formalism, no important superstructure, no Ph.D. in grammatology. I stopped using periods and capital letters to begin new sentences because I haven’t the time. Screw convention, measured breathing, jam and croissants, the contemplated stanza, do I break here or here, how much white space, is it poetry or prose. My psyche’s hemorrhaging, emotional blood’s gushing. Goddammit, I’m hit. I’m trying to save my life.

(Surely “form” solidifies subject, is in fact subject, as subject is in fact form. My “form” is the brick of terror, guilt, shame, pain, horror, hope, rage, love, and innocence jammed into my head, square, compositionally shifting, and lodged like a bloody bludgeon I can only exorcize it by duplicating it on the page, repeatedly and, perhaps, eternally.)

SELAH SATERSTROM: I wonder what you look at or listen to: the necessary juxtapositions that inform your process.

GORDON MASSMAN: I revere great world cinema . Among my favorite directors are Imamura, Fassbinder, Herzog, Bergman, Varda, Passolini, Cocteau, Dryer, DeSica, Wertmuller, Satyajit Ray, Fellini, von Stroheim, Bresson, Schoendorfer, Resnais, Bunuel. Some of my favorite movies are The Passion of Joan of Arc by Dryer, Aguirre, the Wrath of God by Herzog, Salo, or 120 Days of Sodom by Passolini, 8 1/2 by Fellini, Shame by Bergman, The Ballad of Narayama by Imamura, Woman of the Dunes by Teshigahara, Au hasard Balthazar by Bresson.

Elias Canetti, Naguib Mahfouz, Vladimir Nabakov, Borjes, V. Woolf, Mishima, Kobo Abe, Musil, George Konrad, Calvino, Kenzaburo Oe, R. Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, Alan Paton, Nicanor Parra, R. Jeffers, Ted Hughes, Alan Dugan, Berryman, Sexton, Whitman, Dostoevsky, Laxness, Hamsun, Kafka, James Wright. . . . I have a love affair with literature and in addition to “the classics” seek out esoteric obscure works in translation wherever I can find them. I favor creative artists of all genres who dip their instruments directly into the gut, bypassing that cool, objective, distant intellect. I prefer interiors to exteriors, juice to dry, messy psychological eviscerations to cold perfectionism.

I rarely listen to music but when I do I almost always return to sixties and seventies rock: Zeppelin, Hendrix, Cream, early Santana, CSNY, Jefferson Airplane, Joplin, The Doors, Ten Years After, Quicksilver Messenger Service. I love the Chicago blues and Jazz but don’t know much about them. I don’t understand classical music and am continually mystified by how it fills enormous music halls generation after generation with such passionate devotees. But this is my failure.

I am a tireless devotee of the arts and just wish I had more time to explore them.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: In your poems life is a serial killer. Is the trauma he inflicts primarily mental or physical?

GORDON MASSMAN: Physically, I’m in good shape (well, cancer survivor) for a sexagenarian. Mental.

But, short of some heinous assault against one’s person, I don’t think life is a serial killer. I think life (nature, existence, breathing, feeling) is wonderful. For me the serial killer resides within, with only one victim, who keeps getting up.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: If you can't adore a woman and you can't hate her, what can you do with her? I really want to know.

GORDON MASSMAN: Confusion here, one that has caused me much unjustified criticism and, from my partners, pain. The confusion is this: I am my poetry. I am the man who can neither adore nor hate a woman, who tortures cats, who eats himself. I have done none of these things and am not the persona of my work. This is an impossible issue to untangle, it’s as enmeshed into itself as flesh is to veins; it’s all of a piece. Where does artist leave off and persona begin? Kafka, Dostoevsky, Baudelaire, Hemingway: were they beetles, murderers, misanthropes, and misogynists? Yes, that is—partially—their conceit, but were they that as companions and compatriots. As lovers?

On the basis of my writing I have been rejected by women who otherwise loved me. “I cannot stay with a man who could write this,” they said, attributing more life to my poetry than to me. My work frightens them even though, as witnessed by the fact that they love me, and by their own admission, I am not a frightening man. My poetry embarrasses them and shames them in public. They hide it from their friends. To this I say, if you cannot understand the complexity of art and artist, confuse him with ink and white paper or paint and canvas or iron and sculpture, then, yes, I think we are ill-suited.

What I can do with a woman is love her in the same flawed imperfect way all lovers love, even better than some.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: If "vision is puncturing," is the goal of poetry the blast or the emptiness after the blast? Which is more important?

GORDON MASSMAN: That’s a sexual question: orgasm vs. after orgasm, so I’ll answer it sexually. If the poem is like a love interest—you woo her, you romance her, and then, maybe, you have her—then for me it is the instant of penetration, the exhilarating instant of grasping those last words.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: Is the lasting flaccidity of an executed idea really something to aspire to—turning boner into bone?

GORDON MASSMAN: Sometimes the flaccid man is lying alongside a suddenly conceived woman. It is delusional, of course, to equate a work of art to a fetus, but your assumption that once finished the work is a lasting shred of flaccidity is invalid for me.

When young I aspired, romantically, megalomaniacally, to write something so real it lived, that the pages of my theoretical book would groan to get out and actually bounce up the covers like a coffin lid. I wanted to create something so honest it squirmed with new life.

I don’t believe in the flaccidity of a finished work—I aspire to write poems that embody enough “life” in them to conceive in the lives of others.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: If you can't love men and you can't kill men, what can you do with them? I really want to know.

GORDON MASSMAN: Two and a half decades ago I lunched with a certain radiant and conceited young male sociology professor at his faculty club (U. Wisconsin). Menus in hand, we were greeted by a stunningly gorgeous waitress. “Bring me the roast beef with vegetables, and a Coke,” said he. I said something similar, maybe “Baked chicken, white meat, tea.” When she left he raved, “Beautiful, amazing, ooo-la-la, must have her, who is she, think she’s a student, see the way she looked at me, she noticed me, that ‘I’m available to you’ look, she’s mine, I know it.” I agreed, “Adorable, excruciating beautiful, did you see those ankles, those feet, those perfect toes, oh man.” Then I looked him in the eye and said, “What if she prefers me?” A bullet entered his brain. “Then,” he said, “I would have to leave the table.”

In matters of sex and love men are each other’s rivals. If both want the same woman, then they hate each other and it is an unendurable pain not to be chosen. The greatest pleasure is lost to the rival and the loser graphically visualizes the other receiving it, the wetness, the kisses, the caresses, the wonderful penetration.

In a locker room naked men simultaneously feel solidarity and repugnance. They dare not accidently touch each other in the shower stall without feeling revulsion, that competitive matted body hair touching me. Their dangling weaponry. It’s an animal visceral reaction. All men (heteros, of course) want all women and fantasize destroying the competition.

So, I lie that I am the more desirable in order to befriend men. As long as I feel superior, I find men acceptable companions. My best male friends are in their 70s and 80s and unable to do harm to me.

This is oversimplification as men do have fishing, camping or football buddies, but I think the deeper animal primal rivalry lurks underneath it all.

What do I do with men? Depending on the man, I screw up my psychology and behavior therapy strategies and try my best to enjoy their company. In many cases, I do.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: Are you the Sam Kinison of poetry?

GORDON MASSMAN: Without the humor, unfortunately.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: Do you love? Are you loved?

GORDON MASSMAN: I’m self-critical and insecure and find it difficult to believe that I am loved. Yet, I feel loved by one or two.

I subscribe to Eric Fromm’s concept of the word “love” (in The Art of Loving). Loving is an art to be practiced and mastered. To succeed one must make it his or her highest priority. Most fail. Most flounder in passive pools. I believe that, at sixty, after dozens of attempts, I have learned to love, passably, acceptably, maybe even beautifully. I do believe that loving is human beings’ most divine calling. It’s just infernally hard.

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: Why don't you just fucking calm down?

GORDON MASSMAN: Don’t think there’s a why here. When the fire burns up all the wood, it will die. I guess there’s still wood.

(I am calm on the outside.)

ANA BOŽIČEVIĆ & AMY KING: (How) do you think life translates into poetry? How much is it a question of translation and how much of transmutation/alchemy? Does the voice in this book suffer because he is not an alchemist?

GORDON MASSMAN: Lead into gold, transmuting sinful human into perfect being, creating the panacea. No, I have not done that. I go into my gut and amygdala (base instincts, drives, motivations, urges, fantasies, reptilian capabilities). There once existed alchemists, the finest in the land, who perfected the art and against whom present-day alchemist-hopefuls can only be derivative. I speak of Keats, Shelly, Byron, Rumi, Blake, Wordsworth, Dante, etc. My voice certainly would suffer were I to try to emulate these alchemist/masters. They had their pre-Freudian day of courtesies, formalities, corsets, class punctilio, platitudes, meticulousness, generalities, and narcissism. We have our post-Freudian-Einsteinian day of nihilism, nuclear fission, hedonism, birth control patch, gluttony, environmental destruction, and postmodernism. I write for my day and do not suffer that I, or my persona, is not an alchemist. Once it was transmutation, now its translation.

1715

It is unimportant to me whether anyone reads these poems / or their assessment of them should they, I do not care under / whose name they are published, nor could I care less what / literary critics say about them, praise or condemnation, / nothing could be more vapid than some academic advanc- / ing his career on my efforts or within institutionally accept- / able parameters pushing my reputation this way or that, / most contemporary poetry is shit as is the industry that sur- / rounds it and I want no part of it, if I am harsh so be it, if / I am angry then that is life, if I have hurt my consanguineous / they are co-conspirators in their pain, nothing in this work / bears false witness nor have I broken one commandment, / I am a decent man imbued with a religious spirit and cap- / able of love, I have noticed the world is full of cowards.

1711

So here you are in my room, so shove it up your ass mr. big shot, / skull & bones, scythe man, spider fingers wrapping big mouth / round lymph glands or brain matter, mr. infirm eater with gap- / ing jaw, haw haw haw, who’s under your rustling cape but an / empty groin, hole for cock, coccyx kook, go pester elsewhere / the Chesterfield lung, the homicide’s hypodermic ride, go fuck / yourself, I’ve eaten oatmeal enough to fill a lake and univer- / sities of fish, I shit every bloody day and hydrate like a drain, / drive a bucket of balls thrice every seven days, so blow it out / your ass, you’ve come for me, fine, be done with it, I joghead, / I weightpump, decapitate me then like a sour grapes cricket, / you fuckbutt, what do I care, you stink like a port-o-potty, / slit me, slip out my spine, flounder, bull red, speckled trout, / leave aplate the rotting white meat of me, butter soaked, / coagulate, head in the trash, after this freeze my sister like / a genital wart, snow her into the john or underpants, flecks / on flecks spotting the water, fall leaves, wet streets, tire tra- / cks on stuck yellow, with her ribs pick your teeth, blowhard, / I poke a finger through your noneyes, gossamer sockets dry / as bleached pelvises, meatless pig, I jack off in your sky- / wide mouth, boneless bones, electrical zero, collector of the / gorgeous impotent pathetically enhoused mortal valkeries.

1624

First we plunge knife into dog, she fell to knees, toppled, lay / like any meal in gravy, spotted tongue, then baby Lulu, thirt- / een months, pillow over face, pressure, turkey before baking, / extracted pussy by back legs from cabinet, beheaded him, / whole head glued to chair like shish kabob, marinated head- / less body in loggy toilet bowl, you sliced my clothes like / gutting fish, whack whack cling, strips, I lopped your bras / for mastectomy, slashed French panties like jelly crea- / tures, we eyed each other, “love,” you said, “love,” I assented, / “screw you,” you said, “agreed,” I chimed, “I despise your / mother,” “yours drank herself dead,” “None will adore / you like me,” she warned, “Echo,” I responded, one by one / we pulled the feathers off Dante our Parrot, poor Dante / caged and fruited like a bauble, several primary feathers / plucked killed him like a shot weight, claws clutching a / finger, “monster,” she screamed, “Frankenstein,” I fired, / “piece of shit,” shot out the canon my mouth, bereft / of pets and babies her wishbone glittered like a lit ship- / sail, meathooks, striations, bruise red bloomed in my / mind, psychopath, maniac, she studied me like a cannibal, / and down we tumbled in a flurry of slurp, boner, juice, / and squish, slacks and shirts collapsing like parachutes.

1562

Dear God, I wish to register my unhappiness about a few things: mor- / tality is a crock of shit, I could pop you in the mouth for that; gen- / ocide sucks, you deserve a penitentiary gang raping; what about cer- / ebral palsy? hanged by the neck, my good man, hanged by the neck; / I’m a little discontent about mashed teenager canon-fodder wars, / you know, blown off limbs and heads , amputated appendages, / post traumatic stress syndrome, freckled unwrinkled babies mud- / trudging, one could fucking kick you in the gonads or plier them / off like taffy and feed ‘em to chickens, here chick chick, you cel- / estial amateur, scratchy violinist botching Bach; the little matter / of pederasty, the constitutionally sour buggering preadolescents, / or fucking itself between consenters whipping themselves lee- / ward-to-stern chasing that momentary dopamine-filled squiggle / infusing emptiness shame hunger megalomania and finally spir- / itual death, smashed in the kisser, banished, bibles burned simul- / taneously like flushing at once a skyscraper of toilets, bloody / nutcase; what about space travel, you serve up famine, they / booster to moon in million dollar foil suits to tramp around, / demigods to television applause, famine’s worth decapitation, / (I assume neck not in ass a blade can find); oh boy peanut / brickle Lucky Charms Mars AIDS Coke, finger-poke out / your eye, sanctuary fornicator, superstition wrapped in faith / wrapped in fear, Mr. Potato Head; I’ll praise you this; blood- / covered morsels ceaselessly bursting, new beautiful victims.

1379

Huey, Dewey, and Louie bring home three whores for dinner. / Huey gets spanked and blown, Dewey’s a blind patient at the / doctor’s, Louie does it dog style on the sheepskin throw, three / women contain duck come like mechanically filled mustard / jars. How they worship zooming tits, purchased lips, the soft / slot machine of the naked woman. A stogie turns Huey green / poor mallard, night’s growing sour, the promise of vomit, / frankly diarrhea’s looming in guts of three like bruisy storms, / but hell we’re men aren’t we? gimme a Pabst, and red be- / tween the orange webs sucks off his purple cock, and even- / ing drags, dies, the females split, the males blacked out, ash / trays, tumbler rings, mixer packets, missed chunks, Donald / and Daisy anticipating an after the movie tumble pissed at / the profligate nephews, sailor suits and menstrual blood. Don- / ald to Daisy: God dammit! Daisy to Donald: fuck! Donald / to Daisy: Look at this shit. Daisy to Donald: Idiots. Dish- / washer filled, blender upright, the boys covered in blankets / where they lay, Daisy fucked Donald hell for leather till / both sets of genitals failed with satiation, Donald stunned / with love, penis a limp sore biceps, Daisy drunk with semen, / inside out like a flaccid flower, hiving for conception, both / fired and blown apart, hinged at the knees. Oh Donald, Oh / Daisy, Oh Huey, Dewey, and Louie, swaddled, lifted, and / held by God, suckled on heaven’s nipple, do not sob the flesh- / y mess of eggs and lust, sperm and hurt, the slimy floor of / booze, musk, and promises; sleep, safekeep, angels angels angels.

1316

Against my will, I rip down zipper, shove porno before face, grow / tumescent, and rape myself. Rapist fist-squeezes, tears undercircum- / cision tissue, violences orgasm into toilet, and bangs away like a / striking hawk leaving me on carpet weeping. Crisis response team, / rape squad, description (shot sharded glances in mirror), unrpedic- / table, unexpected, brutal, Caucasian, fled into the night of self, vast, / anonymous like a whiptail; rage, not sex; revenge against distant / abusers; howl in heart; injustice gnawing cerebral wires; I’ve not / confessed—shame—he’s hit before, cracked open hard core and / beat incessantly ripping out my stuffing and fled like a murderer / into my soul, slaked on subjugation and spermatozoa. I can take / victimization by his hunger no more, the horror, the shock, the / degradation amidst a beautiful world, his closet appearance ir- / repressibly, he’s always within dead bold perimeters, his shoe- / toes replicating mine and the gutturals wrenched out his throat / iterate details he could not know; Karen’s tampax, Sheila’s lub- / rication, the exquisite blood orange and yellow pipefish, the / unexpurgated yank through caverns of emptiness, cravings of / Joyce, weird tectonic schisms in the earthplates of stability; my / superinformed assailant confusing me with identification; smash- / ing my dick between fist with jackhammer-aching arm, he hal- / lucinatorily grunted, “fucker, you are me,” then incomprehen- / sibly vaporized the instant my come blew me off its string; pride / terrorizes—I’ve slaved, I confess, for years, homosexually, pain- / fully, grievingly, plumbing swallowing my esteem; the tidal sucks / off a devastation-home. No more: hazel; six feet; gray wreath- / tonsure; straight teeth; cupcake mole, left shoulder; moustache; / olive; one-ninety; deceptively soft spoken; black bush; left lobe / crease; fiftyish; big fingers. Grab handful of flesh, wrap fist, rip / him through sewer grate to light, to justice, imposter, fake soc- / ialite, slime-liar, hit/run impresario, abominator of stainlessness / and gorgeous stacks, chickadee household blackguard bastard.

1262

Dear God: thank you for the physical beauty in the world, etc. / and get fucked. Brutality festers under veneer. Abercrombie / and Fitch and the other even-cornered orderly little boxes at- / op the cauldron of rage. I’ve read your absurd prevarications, / burning bush, parting sea, water to wine, the whole bloody / idiotic litany. What do you take me for? My son’s in jail, my / parents hate each other, and love is the biggest crock of shit / in our world. Take it up the ass mr. big. I shove it in and / squirt my ever-regenerating fascist through your anus. You / “work in mysterious ways.” Sure. Gotcha. Like multiple / sclerosis, cerebral hemorrhage, schizophrenia, ovarian can- / cer, gang rape, endless battlefield slaughter, hunger and / starvation, crack cocaine, mandatory economic survival, / family annihilation, serial killer, christmas eve, the whole / bloody genocidal mechanistic panoply of madness, dema- / goguery, power-lust, and blood papered over with The / David, Notre Dame, Starry Night, The Cello Suites, The / Divine Comedy, A Night at the Opera. You don’t fool me / with your poured concrete. The devil created you. Oops! / a brief eulogy-interlude for my latest decimated friend—bone / cancer—chemotherapy, steroids, morphine, marrow trans- / plant—closed his lids on two blonde daughters, 9 and 13— / hole in air, let me chant: HeyHeyHeyHey, HeyHeyHey, / Hey, Hayi-o-ku-oo, tum tum. Thank you mr. zero for an- / other picnic in the park. And he believed! But we know / the irrefutable; invisible wasp with hypodermic stinger whir- / ring through walls, money, steel, petition to jab it in the / neck. “Come down, Come down, why dost thou hide thy / face?” one frustrated poet begged. I will reveal. The mere / hideous outline of you visible would decimate all animal / hope or happiness. You think my personal circumstances / blind and embittering? Don’t make me laugh. I observe / with microscopic scientific objectivity the botanical, zo- / ological, and geological, and state with emotionless inan- / imacy the incontrovertible: I could wedge a baseball bat / up your lower orifice, swing, and Hercules-hurl you to / plague another planet-island of cripples and cruciality with / your miracle-laden-liturgy and it would take a lifetime of / restitution to clean the crap off the end of Louisville wood.

1158

Sewed two cat heads onto my chest for breasts, black, whiskered, / one chartreuse, one amber eyed, mouths fixed in terror-grimace / (decapitated them alive, naturally); fixed a pig snout into my crotch / for cock, raw, red, jagged, but eternally erect; coconut shell pieces / for kneecaps. hairy but tough and sexy; casava skins for butt en- / hancement, smooth, pettable, delicious, pale; slivered banana peel / for hair, long curvy strips with a lilt like a soccer star; the cat / stomachs doubled as moccasins and the pig gut made a fine scrot- / um wrapped round two whole hazelnuts, hanging. Needed a new / heart and decided the ripe red plum, so pried my cavity with a sur- / geon’s vice and stuffed it in, veiny, glutted, sugary-sweet, dripping / deep red streaks mosquitoes could swill on sweltering moonless af- / ternoons; a scooped-out lemon rind for bladder and blown out egg / shell for chin, the kind I smeared Paas over on Easter and called it / art, beaming like a watt; bathed in compost to the crown, stuck / on pheasant and buzzard feathers to ready myself for she for whom / I am cooking shrimp Mozambique with coconut milk, cayenne pep- / per, and Rachmaninoff, she whom by my creole-smooth telephone / voice accepted my invitation sight unseen—the Personals, you know— / and who I am positive will be wearing for playful aperitif thong pan- / ties with the window I’ve seen in nudy magazines. Decided from / ear lobes, to dangle one live goldfish each by needle holes punched / through gossamer fins, a touch, an accessory as Paloma Picasso / would declare, with a smattering of close-to-surface-blood wrist / cologne. I have such a beautiful clean-angled house, roomy, high- / ceilinged, everything squared, spacious, shiny, flat, lacquered, and / wide, and I inside, part ichthyologically glittering, part vegetatively / glammed, mythological, nightmarish, a creature no woman could refuse.

1136

These are the grotesqueries: long fake fingernails painted purple / glued on the end of bitten fingers used to enter minute streams / of data into a PC; a bent and contorted rubber man giving him- / self a blow job on a chintz bedspread at mid-day behind heavy / curtains to a whirring traffic sound in a moderate-sized Midwest- / ern town reeking of sanitized industrial smells and environmental / mediocrity, sucking like a pig his red dong, snorting and slurping / until the gun fires hot flan into his rasping mouth; two average / boobs “anesthetized upon a table” swelling like birthday balloons / as the Master slips silicon heavy pouches into slits wide as or- / gasm-grins, the kind that closes you like a briefcase and slams a / Charlie horse into your thighs, two massive mounds rising from / ash topped with bright red hard proud maraschino cherries; a half / dozen frosted orange vials lining the medicine chest like circus / milk bottles daring to be bowled over, one for nerves, one for / insomnia, one for anxiety, one for bipolarism, one for rage, and / one for love—a puppet theater with a silver curtain behind which / reside Princess Penelope, Queen Prunella, Poh-Poh the Clown, / Hrothgar the dragon and the dastardly Count Badunov each / with their respective handmaidens, henchmen, and courtesans, / all attired in peaked white caps and the family crest across which / is written the prescription for victory; splatting a human brain ag- / ainst the broad part of a bat, particularly if the scalp is Black / and the bat has four running legs attached to and pinwheeled by / a common hip, whose politics ends with the word “premicist,” / if you get my drift, in Bama, Tejas, or Mississip, the bat electrical / taped for grip and discolored with consistently smacked grand / slams against opponents under floodlights to cheering stands, / flashbulbs blinding the victor with grandiosity and capturing on / silver the beautiful slaughter; O the grotesqueries are these: / shoving the middle finger to the ham-knuckle up the anus of / a cat, the cat a frozen sculpture of horror, in the guest room be- / side the closet and wall-socket into which is jammed a light bulb / a lamp a black rubber chord and a two fingered hand; the armless / drummer grinning under moustache in a smoky dome full of booze, / babes, Cobras, and panthers, one strumpet who from a distant pew / coats his body with lust as the cymbals clash, the snares and traps / intensify a rap so hot nothing connects the sticks to his stump but / blurry air or a heat-mirage whose dust flies round a fool diving in; / sinking surgical gloves through fascia and muscle, ligatures and / sheath and striking pure granite, like boulders sunk in silt, granite / arteries, granite gut, granite lungs, granite pump, rock upon rock / in soft mud, immovable, great hereditary tumors imbedded and / petrified into heavy, cold, dead, blunt, blind, unemotional stone.

911

After binging on Dreyer’s butter pecan in a period of / weight gain I went upstairs and almost forced myself / to throw up. I gazed into the toilet like Narcissus. I / imagined slamming two fingers down my throat till / a Vesuvius roared. I felt the weeping of my stomach, / and my accusatory belt. I wanted to kill the monster in / me, the cowardice, the unceasing executioner. Down- / stairs I heard the John Wayne movie: the charging / bugles, the beating of horse hooves, the swirling com- / motion of rifle fire and expiration, all muted by a series / of walls and corners, and in my soft cube, wondered. / I knew that finally I was tortured not enough to per- / forate the tissue of my gut, that I was still a bit of an / hibiscus, that I would rejoin unpunctured my partner / in the film. This brief lavatory interlude was brought / to you by Glamor Magazine, self hatred, pitiful par- / enting, powerlessness, and a rare form of male bulimia.