PHYSICAL GEOLOGY

(A Geological Time Diptych)

cave casts by Ilana Halperin

______________________________________________________

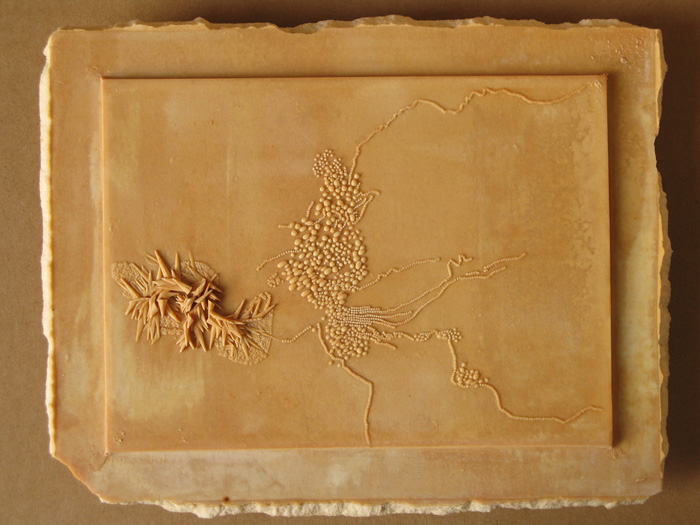

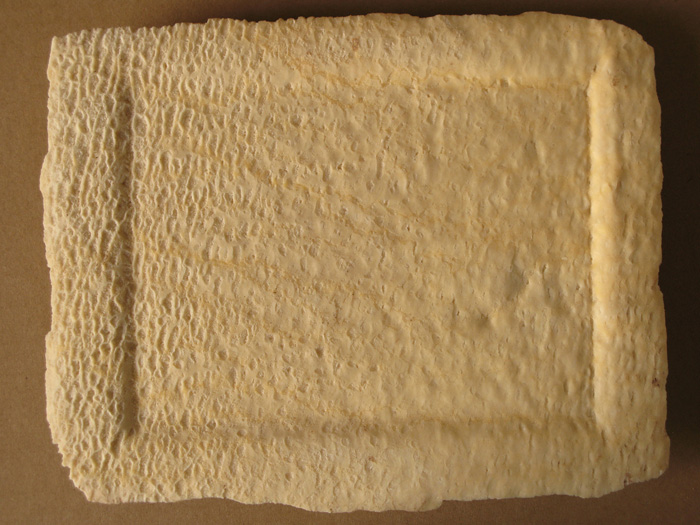

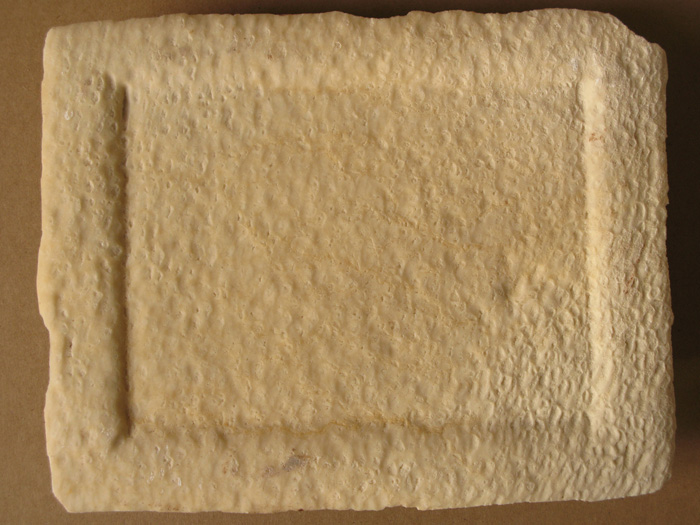

The images below feature a series of cave casts, or 'cast stalactites', formed over ten months in a cave in France. To produce 10 cave casts 25 identical molds were placed in the Fontaines Petrifiantes. Front and back views of five cave casts are included in Trickhouse.

|

|

Please explain this impulse to me –

attempting physical contact with geological time. |

|

| The human consciousness may have begun to leap and boil some sunny day in the Pleistocene, but the race by and large has retained the essence of its animal sense of time. People think in five generations – two ahead, two behind – with heavy emphasis on the one in the middle. Possibly that is tragic, and possibly there is no choice. The human mind may not have evolved enough to be able to comprehend deep time. It may only be able to measure it. At least, that is what geologists wonder sometimes, as they have imparted the questions to me. They wonder to what extent they truly sense the passage of millions of years. They wonder to what extent it is possible to absorb a set of facts and move beyond them, in a sensory manner, beyond the recording intellect and into the abyssal eons. Primordial inhibition may stand in the way. On a geologic time scale, a human lifetime is reduced to a brevity that is too inhibiting to think about. [1] |

|

| Ephemeral islands, petrified raindrops, volcanic dust from Pompeii, a shared birthday with a volcano. Certain geological processes have a way of evoking a more personal response to the idea of geological time. What does a time span of 300,000,000 years actually mean? |

|

| While conducting research as an Alchemy Fellow at the Manchester Museum, in the ‘oddities drawer’ of the geology department I came across a fine collection of lava medallions from Mount Vesuvius — magma pressed between forged steel plates to form an imprint (imagine a waffle iron that uses lava as batter). In the same drawer, a small stone relief sculpture appeared to be carved out of pure white alabaster. In fact, it was a limestone cast created via the same process that forms stalactites in a cave. |

|

| In re-visiting these historical geological art processes (lava forging and cave casting), I began to develop ideas for ‘physical geological art works’ - art objects formed within a geological, or deep time context. |

|

| I went to Saint Nectaire, a small thermal town in the mountains of the Auvergne in France, to meet with Eric Papon, whose family founded the Fontaines Petrifiantes, and the art of cave casting, seven generations ago. In a normal limestone cave it takes 100 years for a stalactite to grow 1 centimeter; in caves of the Fontaines Petrifiantes 1 centimeter grows in 1 year. Every year Eric and his assistant facilitate the formation of hundreds of cave casts through a labor-intensive process involving 25 meter high casting ladders, carbonate waterfalls and natural rubber moulds which slowly fill with limestone deposits over the course of a year. In 2008 we began to work together in the caves. |

|

| The cave cast can be likened to a drawing, a record of incremental change. It is a cousin of the long exposure found in pinhole photography; the gradual accumulation. Though a cave cast serves as a ‘stand in’ for deep time, 12 months are not massive in a geological time context, in daily life – a lot can happen in a year. Within an arts context, a year is also quite a long duration, a continually occurring process forming a piece of work. |

|

| The plan is to make a geological time diptych – new lava medallions, new cave casts – slow time and fast time alongside each other. To date, I have made a new series of cave casts which formed over the course of 10 months in the calcifying springs of the Fontaines Petrifiantes. The last casts were cracked open to coincide with my 36th birthday in September 2009. The slow time component of the project is now complete. |

|

| Ancient and technologically advanced modes of production were employed to arrive at these unique objects of pure geology, including traditional copper plate etching, virtual 3-D modelling, rapid prototyping and limestone encrustation |

|

| But at what moment does wood become stone, peat become coal, limestone become marble? [2]

In a volcanic prologue to the fast time component, I spent time encountering active lava flows as they formed new land on Big Island, Hawaii. To complete the project, lava stamping implements are ready and waiting for a molten river to emerge from another volcano - Etna, where the art of lava forging emerged. This may occur in one moment or within a lifetime. |

|

END NOTES

[1]From Getting the Picture by John McPhee.

[2]From Fugitve Pieces by Anne Michaels |

| |

|

|